| |

There were already 50,000 Chinese in California by 1867, and the Burlingame Treaty of 1868 allowed further immigration, with all possibility of naturalization denied. But Crocker, the great wheeler-dealer, perceived that he could hire men cheaper by sending for them overseas. Besides, his railroad had become an ogre to the resident Chinese, a monster that gobbled them up alive.

The Crocker coolies, happily ignorant of the work's frightful reputation, streamed in from South China until a total of 3,000 were laying out the Central Pacific's lines.

Contrary to a popular notion held at the time, the term "coolie" did not derive from a corruption of "contract laborer." The British (coiners in Egypt of the insulting "wog," an acronym for "worthy Oriental gentlemen") had adopted it in India at least a generation earlier. It was actually a proper Hindi word, quli, meaning "hired servant," that traveled to Hong Kong in 1842 when China ceded that island as a British Crown Colony. Thence, it continued its journey to California with the boatloads of contractees.

Hoping to improve their lot in the New World, the coolies worked harder than Crocker ever dreamed they would. An innovative mind among them evolved a method of implanting explosive charges in the High Sierras' steeps: Chinese men swung down the cliff sides in wickerwork baskets suspended by ropes and did the job from there. It was dangerous work. In record time, they hewed track beds from solid rock and pushed from California to Promontory Point, Utah, to meet the westbound crews. They accomplished a magnificent feat.

The final, ceremonial spike physically joining the United States into one great unit was made of gold. That aureate nail may have represented the only gold that most of the coolies would ever have seen in the land of Golden Mountain, but even that simple privilege, like most others, was denied them.

White prejudice excluded the Asian workers from the ceremony and the jubilant celebrations which followed the coupling of the lines on May 10, 1869. It is not recorded how they took that news, but one may assume they received it in stoical silence, and in translation, from a Caucasian boss. Then, one hopes, they found pleasure in congratulating each other over strong rice wine or an equally good whiskey.

The harsh conditions had taken a terrible toll, but every spike the Chinese drove into American soil nailed them more firmly to the country that generations of their progeny would call home. In only four years, they had finished the most challenging stretch of the marvel of the age, the transcontinental railroad--an iron serpent twice longer than the Great Wall.

Figuratively speaking, neither wood nor coal fueled the locomotives that coursed along the rails and steamed triumphantly to the shores of San Francisco Bay; it was the sweat and blood of courageous, and ultimately wronged, Chinese men that sped them on their way.

The railroad was not the only fruit of Chinese toil in California.

Asian workers reclaimed the swampy deltas of the San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers. They developed a system of levees and dikes that even today protect the fertile fields from encroaching waters, lending a look of Holland to the landscape, sans windmills. Then they went to work as farmers on that very land and produced the bulk of food supplies for Northern California.

As late as the 1870's, more than 70 percent of the agricultural laborers in the state were Chinese. Not until the 1890's were they replaced in number by the Japanese.

Fishing camps up and down the coast were primarily manned by Chinese, the first commercial fishermen in the state.

They discovered the abalone in Monterey Bay, a shellfish delicacy much prized by gourmets.

San Francisco's famed Fisherman's Wharf was developed under the tutelage of the Chinese until a tidal wave of Italian immigrants engulfed it with another ethnic identity.

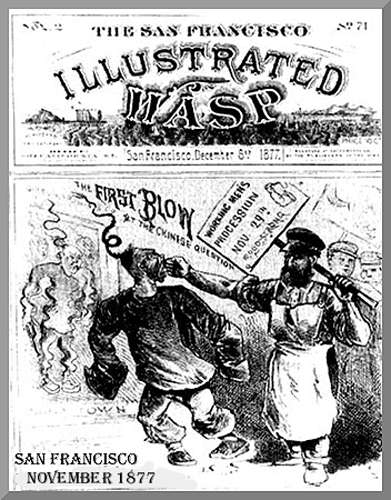

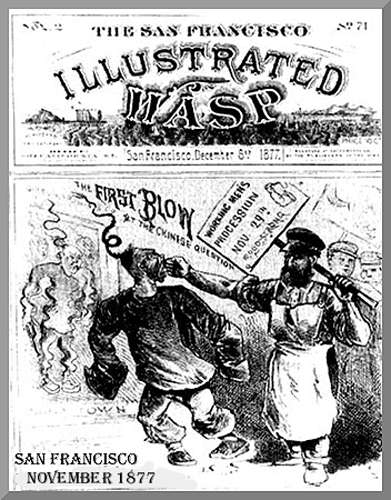

Despite the innumerable successes accomplished by the Chinese, the doctrine of white supremacy nurtured continuing animus against them. In 1872, the Chinese fishing boat, the junk, was declared a foreign vessel without right of passage through American coastal waters. With competition for jobs the excuse, but racial prejudice truly the cause, riots against the Chinese, and Asians in general, broke out in San Francisco in 1877.

The U.S. Congress took up the cudgel in 1882 and passed legislation banning normal Chinese immigration for 10 years. Only marriage and family connections could set the law aside. Renewed in 1894, the law was hustled through again in 1924, but with a provision implying that Chinese residents in America were forbidden to buy brides from China, a traditional practice which had made thrifty savers of lonely men who might otherwise have wasted their substance on other things. Its side effect was the spawning of a generation of bachelors, a phenomenon later to become familiar to all the "old Chinatown hands" the San Francisco Police Department would spawn in the next 40 years.

This came about because the law of 1924 forbade the entry into the United States of Chinese, as well as most other Asian, immigrants who already had family connections in America. Ostensibly, that was meant to cover everybody from Tokyo to Bombay, and, by inference, all the way to the Bosporus, a strait about 18 miles long between Turkey in Europe and Turkey in Asia. It's target, however, was the Chinese and, thus, no loophole was allowed for a bought-and-paid-for Chinese bride to come in from Hong Kong, Manila or Kuala Lumpur on another country's quota. The screw could be turned no more, short of repatriating Chinese-Americans to the land of Chiang Kai-shek, rising power of the Kuomintang, the ruling political party of China.

The Second World War forced the screw to even that sorry turn for many Japanese who considered the United States their home--not repatriation to China, naturally, but back to Hideki Tojo's Axis Japan. This time, the Chinese, now American wartime allies, escaped the lash. Even so, not until 1943 was immigration from China re-established. A quota was set at 105 people per year. The new law carried a bonus; resident Chinese were permitted to apply for naturalized citizenship. Thousands did.

Through those long years, from 1882 to 1943, the Chinese remained undaunted. Entrepreneurs emerged from their ranks. One developed a new variety of rice and established a thriving industry. Another bred the Bing cherry that bears his name. Men of vision found fortunes in self-created opportunities.

In the 1860's, a consortium of the most successful had been formed to consolidate and protect Chinese interests. It called itself Luk Dai Gung See, or the Chinese Benevolent Association, better known later as the Six Companies. The organization, founded by the Chinese agents of six Hong Kong companies that had channeled Crocker's coolie trade through the Crown Colony, came to hold absolute sway over the Oriental business community and, by reflection, over San Francisco's booming Chinatown.

Despite such setbacks as the Federal Asian Exclusion Act of 1882, the Chinese merchant community prospered, meeting the need for service to its own kind, as well as to the emerging San Francisco taste for oriental bric-a-brac, neatly pressed laundry and exotic cuisine.

The Chinese persisted in their efforts to rise higher. They saved money to buy brides from China to join them in achieving their great hopes for the future. Although economic and sociological strides were made as family units developed, endless prejudice confronted them. While the Chinese began to acquire the material trappings of mainstream California life, nonetheless their enforced aloofness was interpreted by white society as an air of mystery pervading the warren of alleys in San Francisco's Chinatown.

Rumors abounded that there were secret tunnels underground. It was said that right under Portsmouth Square itself ran arcane passageways hiding untold horrors from Occidental eyes. The honest reputation the Chinese had earned in the past by tunneling through mountains was perverted easily in an atmosphere of bigotry to a notion that even though "Charlie Chinaman" might appear normal when walking along Dupont Gai--Chinatown's main thoroughfare before it became today's Grant Avenue--evil had to be lurking somewhere nearby.

True enough, there were dank opium dens in Chinatown where a "Celestial" could escape reality in fantastic dreams, but it was also true, for many potentially productive citizens of Chinatown, that the odious reality of sweatshop labor conditions drove them to the dens. Most, however, eased daily humiliations with the consoling pastimes of family life.

There was, moreover, the evil of girls smuggled in from China to be forced into the abject and literal slavery of prostitution. That their clientele was often exclusively white was beside the point to some City Fathers and others who decried such immorality and blamed it on the Chinese, while ignoring similar traffic involving Mexicans and other foreign nationals.

Few voices cried out in that wilderness except Donaldina Cameron's. The pixilated exploits of the lady missionary-cum-crusader thrilled San Francisco's polite society at the turn of the century--and also earned her the honorific title Lo Mo, "Old Mother" (of Chinatown).

A wise and effective do-gooder, Cameron saved countless young Chinese women from uncertain fates and gave them opportunities to lead useful lives. Her memorial is the antique-brick Donaldina Cameron Presbyterian Mission House, a thriving social center for Chinese young people, at the corner of Sacramento Street and Joice Alley in Chinatown.

During the 1860's, Tongs had consolidated their power among the gangs of railroad workers. Uniquely Chinese-American, the Tongs had first appeared as very low-profile groups of Chinese strongmen hired by the Family Associations to protect members from white men and other ethnic groups who preyed upon them in the gold fields.

Based on the Triad system of secret societies traditional in China, the Tongs began to flourish publicly as social centers in the 1880's. By then, the Asian Exclusion Act had finally convinced America's Chinese that yellow was unquestionably one of the lower layers in the pousse-café of races--black, brown, red, yellow and white--inhabiting the United States. The blows from the Congress of 1882 and from San Francisco's white citizenry in 1877 had left no doubt about which race comprised the color-free whipped cream on top.

New arrivals who found no place in the Family Associations gravitated toward the fraternal Tongs. Having already operated in the shade for decades, the Tongs easily fell back on the "paper-son" principle for recruitment of members direct from China; immigration paperwork would be adjusted to include the "sons" of "fathers" whose connection was seldom biological. As the Tongs acquired larger membership and, thus, more power, they initiated or took over most of Chinatown's illicit activities.

On Nob Hill, a name thought to be a corrupted form of "nabobs' hill," the mighty of San Francisco built opulent mansions. These baronial residences cast long shadows down the eastern side of the hill, over Chinatown, where the majority of Chinese diligently plodded through the slough of prejudice that made so many of them unemployable, but hoping to gain, eventually, higher ground. Many went into business for themselves, discerning commerce as the only route to follow.

The Great Earthquake and Fire of 1906 destroyed Old Chinatown, and Old San Francisco, as well. But neither the Chinese nor other San Franciscans allowed the temblors of the San Andreas fault to dampen their will to survive. From the ashes, phoenix-like, both rose again. Gone forever were the streets as they were, but Chinatown had lost nothing of its mystery for the white man, nor its barrier against a hostile society--the wall of silence.

|

|