| |

"Is he dead? So much blood! Is he dead?" María's voice hammered in my ears, dulled only by the screams of Paco's mother as she raced toward us from the Gypsy camp.

"My son, my angel!" the Gypsy queen cried, throwing herself to the cobblestones of the street beside his limp form.

Kneeling down, I instinctively reached for his wrist to find a pulse. My instincts did not serve me well. Paco had no wrist! He had no arms or legs except stumps! From the neck down, he was mostly torso, and not much of that, being a small twelve-year-old.

I found a pulse at his throat.

"He's alive!" I said. "José, go after the Jesuit. Ask him to bring the school doctor at once."

I knew nothing of the medical facilities in the town, but I did know that the exclusive boys' academy in the central plaza staffed a general practitioner of some worth. The students came from the wealthiest families in the country. The sons of Mexican oligarchs would hardly go without fine medical care.

I lifted Paco gently in my arms. His mother followed me into the house where I placed him on the bed in a guest room. Maria ran before us to throw a thick serape, like a blanket, across the coverlet so the boy's blood would not soak the sheets. He had little more weight than a pillow, I thought as I lay him down.

José returned shortly with my Jesuit and another religious in tow, an older man.

"Father Mateo is a Spaniard, like me," my Jesuit introduced him. "He is a fine doctor."

"The boy has bled all over your clothing," the doctor noted.

"Take no thought for such things, Father," I said. "Give us back our boy."

The Gypsy queen, subdued and clutching a rosary in her hands, sat down in a chair near the bed, drained by the emotion that had swept over her in the street. María stood beside her with a hand resting consolingly on her shoulder. Both women were crying softly as the doctor cleaned and studied a series of bite wounds.

Our Paco seemed pathetically small against the wide expanse of the bed. He looked at that moment like the model of a young Aztec prince I had seen in one of several dioramas at a museum in Mexico City. The Aztecs had sacrificed the lame like Paco to their gods in those days. Similarly, he may have been sacrificed in modern times for his lameness when the Indian woman who bore him left him on a mountainside to die.

"There's been no rabies here for years, and he won't die of the wounds inflicted by the dog," Father Mateo announced to everyone's relief. "He has no more than fainted from the terror of the attack. I'll give him an injection to assure a good sleep. Rest is best, I say. But there is another problem. I must address the parents of this lad."

I indicated Doña Concepción. The doctor was taken aback. "Surely, he is not your natural child?"

The queen reddened. "God gave him to me! What is more natural than that?"

Realizing he had committed a serious faux pas, the Jesuit practitioner made haste to correct it: "No, señora, I did not mean it so. What I see is a boy with the features of an Indian, not even the mestizo of mixed race, and certainly not a...."

"A Gypsy," I intruded. "No, Father, he is the Gypsy queen's adopted son. She rescued him from certain death shortly after his birth."

The doctor bowed to her. "May God bless you forever, my royal lady, as He has done tonight. Your son could easily have been killed by that dog."

Doña Concepción, now understanding that the Jesuit had not meant to offend, nodded in return. "Thank you for tending my son, Father. How may I repay you?"

The doctor shook his head. "My payment is that his wounds are superficial. I need only dress them and send him on his way. What happened to your son tonight may, strange as it seems, have been an act of God. Were it not for the attack, I would have been given no opportunity to examine him. I'm glad I did."

He paused.

"His breathing is tortured," he said. "The wheezing--can you hear it? An obstruction is developing in his breathing apparatus due to an increasing curvature of the spine."

I described the way Paco pushed his little cart.

"Ah, that would be the cause!" the doctor concluded.

The Gypsy queen heaved a deep sigh. "Isn't there anything you can do, Father?"

"I've made him comfortable for now," he answered. "As for his condition, it is beyond the scope of my practice. The students at the school are scions of the rich. If one of them were to develop such a problem, his parents would send a private airplane to whisk their son to a specialist in Guadalajara or Mexico City."

He meant that the Gypsies would lose Paco unless something were done at once.

María removed the bloodied serape from the bed and turned back the coverlet. Bandaged and cleansed, Paco lay amid soft pillows and blankets, peacefully asleep. We left his mother in the room with him that night, her chair pulled next to his bed.

He was bright-eyed the next morning, waking early and demanding to be taken from the high bed so he could play with my dogs and visit the crèche. The only reminders of his narrow escape the night before were slight irritation from the wounds and stiffness from deep sleep.

He insisted later on returning to the Gypsy camp to spend Christmas Day with his tribe. I turned down his invitation to join them, insisting, however, that María and José do so without thought of leaving me alone. Lacking only the jingle of sleigh bells, Paco tootled off merrily, pulled on his cart by my dogs.

I spent the afternoon soaking in the horse trough. I could see the crèche from where I lay up to my neck in tepid water.

Unlike a visit from Santa Claus on Christmas Eve, gifts were brought by the Magi on Twelfth Night, or the eve of Epiphany, a misnomer as the Twelfth Day, or Little Christmas, was Epiphany itself..

The strains of Menotti's Amahl and the Night Visitors, a Christmas opera, echoed in the chambers of my mind. Amahl had been crippled, too, but because of his love for the Baby Jesus, the Three Kings gave him a healing. Yes, there was magic for everyone in the gifts of the Magi.

What would they give Paco?

A psychiatrist friend of mine, Felipe, had a first-rate clinic for children in Guadalajara. With others, I had volunteered to help at the clinic until he got fully funded and organized. For three months, I had presented myself twice a week and worked at whatever assignment given me. The volunteers were gradually replaced by professionals as funds became available. It occurred to me by the end of my lengthy bath that Felipe might be able to help.

On the following morning, the queen set out with Paco and me for the hours-long drive to thriving metropolis four hours' drive away. I was thankful I didn't have to get behind the wheel of the old school bus outfitted as a motor home. Doña Concepción maneuvered magnificently around the potholes and goats in the roads, driving with a keen sense of humor, laughing at Paco's witty remarks, until we entered heavy traffic approaching Guadalajara. Then, driving became serious business until at last we pulled up in front of the clinic in mid-afternoon. I carried Paco inside.

We must have made a pathetic sight, the three of us encrusted with dust from the roads, and Paco hanging limp in my arms--an incorrigible joker pretending to be at the point of death. The receptionist cried out when she saw us, running for the doctor and dragging him toward us by the hand.

Passing Paco to him, I explained what had taken place after the Gypsy posada. His chin resting on Felipe's shoulder, Paco chose that moment to open his eyes to give the receptionist a theatrical wink. Her relief supplanted a brief flash of anger. She tousled his hair and kissed him on the forehead.

Felipe surprised me then. "We treat not only mental disorders. I also have a small surgical theater for minor operations. Cases I can't handle are taken over by specialists who are friends of mine."

The doctor grinned impishly. "You remember how good I am at attracting volunteers. There will no bill for Paco at this clinic. Anything we do for him, you paid for in advance when you did volunteer work for us last fall."

The face of the Gypsy queen was a study in gratitude.

Working at incredible speed, Felipe had a specialist there within the hour to examine Paco from top to bottom.

Father Mateo had been right; Paco had been moving quickly toward his end, "but I can fix this boy up in an hour or two," the specialist said. "Get him ready. I will operate now."

Felipe clasped the Gypsy queen's hands. "There is always risk, señora. If Gypsies do have mystical powers, as they say, please use them now. Help us save your son."

"Our only mystical power is the love of God, and that has already guided us to you."

During the proceedings, Doña Concepción and I were given comfortable chairs in the room where Paco would be brought afterward. There were two beds in the small room, one of them occupied by a sleeping child about Paco's age.

"Lucas is a sad case," Felipe explained. "He's my sister's son. I keep him close to me to ensure he doesn't suffer."

I gave him a questioning look.

"He's dying of bone cancer," Felipe went on. "It will happen soon. Usually his mother or father are here, but they've been called away on account of another death in the family. I think Paco's being here might cheer him up for the next few days. Also, since you both wish to be with Paco, you can keep an eye on Lucas, too. He's heavily drugged with morphine most of the time and is seldom in his right mind, but whatever you can do to make him know he is not alone would be appreciated."

Naturally, we agreed to help. He offered us cots to sleep on in the hall, but we declined, finding the chairs comfortable enough.

The boy still slept when Paco was brought in two hours later. Felipe and the specialist took his mother and me into the hall to explain that the operation had cleared his windpipe of a growth which could have killed him in a matter of days had it not been diagnosed by Father Mateo on Christmas Eve and had we not responded at once with the trip to Guadalajara.

"Your son will live, señora," the specialist said.

"Los Tres Reyes, 'the Three Kings,' came early this year," said the Gypsy queen tearfully, indicating Felipe, the specialist and myself. "You've bestowed upon my son a gift of time. I know it will be filled with love. Thank you, thank you, thank you."

Throughout the night, she and I took turns dozing, waiting for Paco to wake. On one of my watches, I heard Lucas rustling his sheets and softly calling an indistinguishable name. Later, it was clear that he was half awake, and I heard a change of breathing from Paco's bed. The room was dimly lighted. Neither boy could see us.

Lucas continued to call out the name. At last, the sound made sense to my ears: "Gitano! Gypsy!"

Obviously thinking that the boy was talking to him, Paco responded in a sleepy voice, "Yes?"

"When I am well, we will run together," said Lucas.

"I cannot run," Paco replied. "I don't have legs."

"Oh, yes, you do! You are my children Gypsy. We will play."

"Yes, we will play."

"We will run and play."

"No, I told you! I cannot run, but we will play. The sausages will run. They will pull my cart. I will keep up with you."

"You are funny! Sausages can't pull a wagon. Besides, it's my wagon. You must pull ME, Gypsy!"

"I mean sausage dogs, and I can't pull you. I told you I don't have legs."

"Ha, ha! Gypsy, you are a silly sausage yourself, but you are a good dog"

"I'm not a sausage! I'm not a dog!"

"You're Gypsy!"

"Yes, a Gypsy."

Both boys drifted into sleep.

The Gypsy queen, stirred awake by the boys' exchange, touched my arm. "My Paco is funny even when he is not awake!"

Shortly thereafter, massively exhausted by the trip and our expectations of worse than we got, she and I fell soundly asleep in our chairs.

I woke with a start early in the morning when I felt a cold nose touch my hand. A very large dog stared back at me. Paco and the other boy still slept. A woman entered the room just then, on tiptoe, and, seeing me, laid a finger on her lips for quiet.

Terrified of the effect the dog's presence might have on Paco if he awoke, I got up from my chair and offered it to her. I went at once to Paco's bedside, just in case. She sat down and whispered to the Gypsy queen, who had also been awakened.

I looked more carefully at the dog. He was a German shepherd of good stock, with a noble head and commanding presence, the type of dog often taken into police work.

He had positioned himself at the foot of the boy's bed. His dense coat ran from grayish to black with overtones of tan. His relaxed attitude suggested acceptance of Paco's mother and me, but I was concerned about Paco's reaction .

When the morning sunlight streamed through the windows, Paco woke up. He smiled.

"Am I still alive?" he asked.

I assured him he was. His mother came to the bedside at the sound of his voice.

"I don't know where I was," he said. "but there was a boy who said I could run. He said I had legs! Mamacita, did the doctor give me legs?"

He kicked with his stumps and tried to lift the sheets.

"No, my darling," answered Doña Concepción, "you are just as you were except now you can breathe more easily. Can you tell the difference?"

Paco took a deep breath, "Yes, but it hurts!"

"The doctor tells us the discomfort will go away in a day or two," I said.

He looked reassured. "The other boy...who was he? He knew that I'm a Gypsy."

Suddenly, the German shepherd pushed between the queen and me to place his huge paws on the bed. His head was higher than Paco's.

Paco drew back in terror like a frightened cat scrambling to climb curtains at a window in frantic escape.

"Gypsy!" called a small, weak voice from the other bed. "Gypsy, no! Come here!"

The dog dropped to the floor and went to lick Lucas's outstretched hand. The woman who had come into the room earlier joined them at the bed.

"Please forgive my son's dog, señores," she apologized. "He thought your boy was saying his name. He is very gentle."

"Mama, Gypsy can talk!" Lucas said with as much excitement as he could muster. His small, bony hand stroked the top of the German shepherd's head. "Really! He didn't understand everything I said, but he really did talk to me. Gypsy, speak!"

The dog sat up on his hindquarters, paws in the air, and barked once.

"No! No!" cried the boy impatiently. "Speak the way you did last night. Speak words!"

Another bark. We had to laugh. I told him about the conversation we had overheard and then introduced him to Paco. "Both of you boys were half asleep. I'm surprised you remember."

Lucas propped himself up on an elbow to get a better look. "You don't have legs, truly? Let me see!"

Paco lifted the covers with the stump of an arm. "I don't lie. What I told you was true. I can't run, but the sausages can pull me faster than you can run with those skinny legs of yours!"

Lucas dissolved in laughter. "Chorizos! Sausages for legs! Funny!"

Paco was furious. "No, goat head! Sausage DOGS! Tell him, señor, about your sausage dogs!"

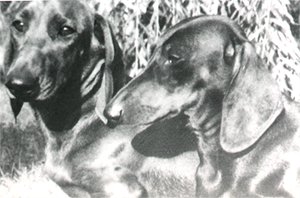

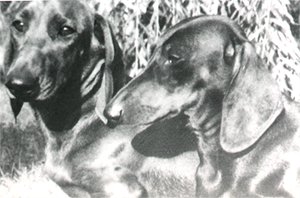

"He's telling the truth," I said. "I have two small dogs who are shaped like long sausages. In Mexico, they call them 'sausage' dogs. In Spain, they call them 'streetcar' dogs, and in Italy, they call them 'salami' dogs. Their real name is 'dachshund.' Here, I have a picture."

As it happened, just as dads carry pictures of their children in their wallets, I had folded away in mine a copy of an international advertisement for an herb pastille that lent a dazzling sheen to a dog's coat. My pooches appeared in the ad looking glamorous and glossy, wearing berets on a Parisian boulevard.

Both boys were equally impressed. I hadn't shown it to Paco before.

Although Paco could have left the clinic on the Fourth Day of Christmas, the consensus was that he stay on for the sake of Lucas. Felipe considered him responsible for the dying boy's surprising rally. It was also good for Paco, whose blossoming relationship with the gentle German shepherd had greatly alleviated the trauma of the black dog's attack.

Lucas had developed bone cancer two years before. When he became too weak to walk most of the time, his parents had acquired Gypsy, who had been especially trained in Mexico City to deal with such children. The dog pulled him about in a wagon to make it seem like a game until walking was out of the question and Lucas was confined to his wheel chair. Gypsy could pull that, too. The boy and the dog had developed an affinity which Lucas's parents believed had helped to keep the boy alive.

On New Year's Eve, the Sixth Day of Christmas, it was agreed that an outing was possible. When he heard I was in town, a wealthy Mexican friend of mine extended an invitation to an afternoon gathering at his estate in suburban Guadalajara. It was ideal for the boys with its gardens spilling flowers into a vast artificial lake. We picnicked on a little island in the lake.

"His body has nearly spent itself," his mother pronounced sadly while the boys sat giggling together under a tree, "but his love for Gypsy renews his spirit every day, and Paco has been a tonic as well. They have both extended his life. Still, the end is near. His time could come at any moment."

Even so, no one was prepared when, two days later, on the Eighth Day of Christmas, Lucas suddenly died. It was as though we never knew it would come to that--the desolation, the pain in hearts left behind. The Gypsy queen and I were not there. We had gone to buy gifts for Twelfth Night. Lucas's parents were with him, and Paco, and Gypsy.

Lucas's mother described his passing to us disconsolately: "My son and Paco were sitting on the bed together playing a silly word game when suddenly Lucas fell back on the pillow. We were outside in the hallway. Paco shouted for us to come. Lucas lay very still, but his eyes were open, and he could talk: 'I think I have to go now. God must need me very much.' Paco lay with his head on the same pillow and would not let us move him away. 'No,' he said, 'I am going with Lucas. I must be here beside him where the angels of death can find me.' I told him he could not go, but he shook his head and pulled himself closer to my son. 'Mama is right,' Lucas said. 'I have to go alone. You must stay here to take care of Gypsy. He's your dog now. He will pull you around the way he pulled me. Mama, you will let Paco have Gypsy, won't you?' Of course, I said that I would. Then...my Lucas...told us...he loved us. And then ....he...was...gone."

We stayed on through the Tenth Day of Christmas, when they interred Lucas. We began the drive back to El Mesón early on Twelfth Night. Since Lucas's death, Paco had not been his usual chipper self. He had worn a back brace since the surgery, and hated it, but the problem was mental. When asked to tell us what was wrong, he barked, "I don't want to talk about it!"

"When does this thing come off?" he asked about the brace.

"The doctor said we should remove it only when you sleep," the Gypsy queen replied. "You are supposed to wear it for the rest of your life."

He sat in silence for awhile.

"Then I won't live very long," he snapped. "Stop the bus. I want to ride with Gypsy."

We stopped, and I carried him to a sitting area midway back where I strapped him into a chair. He begged me to loosen the new brace, but his mother said no. We had to follow the doctor's orders. Paco was an unhappy boy at the moment. Not even a lick from Gypsy improved his disposition. We continued on our way.

"I wouldn't worry too much, Doña Concepción," I suggested. "He has good reason to be out of sorts. He's upset about Lucas's death, and he hates the brace. Everything must look bleak."

She shook her head, keeping her eyes on the potholed road as she drove. "I know my son. It's something more, deep inside. We'll find out in time."

I had sent telegrams regularly to keep the people at home apprised of Paco's progress and of our return. Private telephones were a rarity. Most calls went through central exchanges in each town or to public phones. Hand-delivered telegrams were a useful service.

Everyone had gathered at El Mesón by the time we arrived. Despite the loving reception with kisses all round and endless hugging, Paco remained distant.

My dachshunds had already known and loved a German shepherd, named King, in Italy. He had taught them the lessons city dogs needed to know for country living. They took to Gypsy, and he returned the compliment after a lengthy session of sniffs. Afterward, they all sat quietly together near Paco while María served refreshments. She settled on a chair beside Paco to feed him herself. He shook his head wordlessly each time she lifted food to his mouth, keeping his lips closed. Wisely, she did not insist and gave up after awhile, but stayed at his side.

His depression seemed serious enough for Father Mateo to suggest extra medication.

His mother declined. "I want his mind as clear as possible. He's working something out in his head. It must be solved, or he will suffer even more. He is not like me and the tribe, or like anyone else I have ever known. He has an intensity I do not possess. He taught himself to read and then helped me improve mine. He can learn anything, and never forgets. His powers of concentration have frightened me sometimes."

Has he any formal education?" asked my Jesuit historian.

"Oh, no!" his mother replied. "We are never anywhere more than a week or two. His learning comes from books he reads on the road. Besides, who in this country would teach a Gypsy child with no arms or legs, a Gypsy child who is actually a Mexican Indian of the most despised class?"

My Jesuit touched her arm gently. "Dear lady, there are those of us who do not despise the Indian and who feel that having arms and legs is not necessarily the sign of a good mind. You should remember that the greatest leader this country has ever known was Benito Juárez, a political genius of pure Indian blood. His dark face shines like a white light in the history of Mexico."

Directly, as evening came on, José proceeded to light the lanterns strung across the courtyard. I wondered aloud if the Three Kings might have secretly delivered our gifts to the stable in the corral. Of course, José and María had already placed out there the things we brought from Guadalajara.

Paco tapped María's knee. She lowered her head. He whispered. She nodded. She rose from her chair, lifted him in her arms, and carried him to the corral. A look from María suggested that we not follow right away. I thought she might be taking him to the privy. I asked the Gypsies to honor us with Romany songs. The young girl about to be married sang a few lovely ballads, joined by the others. Then the nuns offered a charming duet of sacred music.

At that point, I heard María say to us from the archway, "He's feeling better now."

The figures of the Holy Family still stood in the crèche which would not be disassembled until the day after Epiphany, which is often the time when Christmas trees are taken down in the States. We found Paco sitting beside the cradle, as he had on Christmas Eve. The lanterns were lit as before, giving the effect of a theatrical tableau. He looked radiant, a complete turnabout from thirty minutes past. I took charge of passing out gifts. There was something for everyone.

The largest box, up to my waist, had Paco's name on it.

"Shall I open it for you, young man?" I asked.

He nodded, his eyes wide. I stripped away the wrappings to reveal Lucas's wheel chair, a gift from the parents of the dead boy. Paco beamed.

"I already knew about the chair," he said brightly. "Lucas told me just now. They've made him an angel, you see, so he makes round trips, now. He said they sent him to tell his mother in what she thought was a dream that God is giving her a baby to take Lucas's place. Lucas will be the guardian angel. They will always be together."

He looked around. Our faces showed clearly that we weren't sure how to respond.

"I tell you, it's true!" he insisted. "I asked María to bring me out here to talk things over with Baby Jesus. He was happy to see me again. Look at His smile!" He nodded at the carved figure in the cradle. "He told me Lucas had been waiting for me, and there he was, right there, sitting on top, shining brighter than these lanterns." Paco indicated the box which had contained the chair.

We all looked at the box expectantly.

Paco laughed. "María couldn't see him, either! He came just to talk to me. He knew why I wanted to go with him to heaven. We had talked about it. He knew I wanted to ask God why was I born like this, why I was made only halfway. I never forgot that my first mother abandoned me, and then, when the angels came for Lucas, they didn't want me. I thought even God had abandoned me. He would take a good, well-made boy like Lucas, but he had no use for a misfit like me. I really didn't like God anymore." An agonized sigh came from the Gypsy queen. Paco lifted his arm stumps entreatingly.

"No, Mamacita, don't be sad! I don't feel that way now! Lucas said heaven did not do this to me. I was meant to be a perfect child. Something happened, but no one knew until my first mother prayed over me when she left me on the hillside. Mamacita, you were the answer to her prayer! You needed me. God knew you would love me. I'm a lucky boy! My job is to love everyone as much as I am loved. That's all Lucas said, except that I have to keep on making the most of what I have, and if any changes are to be made, heaven will make them. Does that mean God will give me legs, Mamacita?"

Doña Concepción lifted him to her bosom.

"What could be impossible to infinite love?" she said.

I asked the same question of myself the following afternoon after being summoned to the telephone exchange to receive a call from Felipe in Guadalajara. He reported that Lucas's mother, in an almost hysterical state, had rushed into the clinic that morning crying her dead son had appeared in what seemed like more than a dream with the prophecy of another child.

A test in the laboratory confirmed her pregnancy. After recovering from the shock of this corroboration of Lucas's visit to Paco, I informed Felipe how it was that we knew about it before he did. Dubious at first, being as much if not more of a doubting Thomas than I, Felipe knew that I would not lie about such a thing, particularly as Lucas was his nephew.

Staying close to Paco and his Gypsy tribe promised deeper insight into a phenomenon about which the late Albert Einstein once spoke of as "the sensation of the mystical," making us want "...to know what is impenetrable to us really exists..."

Given that the Gypsies were leaving on a new tour through the mountains as soon as a fresh inventory of movies arrived from Mexico City, I wondered how to make the most of the few days left together.

The answer came when I returned to El Mesón to deliver the exciting news from Felipe. Paco and his mother were having bowls of María's delicious menudo, tripe soup served with a generous sprinkling of fresh oregano. As I approached the dining area unseen, I heard them ask María if she thought I might consider joining them for the first few weeks of the tour. Before the housekeeper could answer, I appeared in the doorway and shouted: "Yes! Yes!"

I could conceive of no more auspicious way to begin the new year. "He's telling the truth," I said. "I have two small dogs who are shaped like long sausages. In Mexico, they call them 'sausage' dogs. In Spain, they call them 'streetcar' dogs, and in Italy, they call them 'salami' dogs. Their real name is 'dachshund.' Here, I have a picture."

As it happened, just as dads carry pictures of their children in their wallets, I had folded away in mine a copy of an international advertisement for an herb pastille that lent a dazzling sheen to a dog's coat. My pooches appeared in the ad looking glamorous and glossy, wearing berets on a Parisian boulevard.

Both boys were equally impressed. I hadn't shown it to Paco before.

Although Paco could have left the clinic on the Fourth Day of Christmas, the consensus was that he stay on for the sake of Lucas. Felipe considered him responsible for the dying boy's surprising rally. It was also good for Paco, whose blossoming relationship with the gentle German shepherd had greatly alleviated the trauma of the black dog's attack.

Lucas had developed bone cancer two years before. When he became too weak to walk most of the time, his parents had acquired Gypsy, who had been especially trained in Mexico City to deal with such children. The dog pulled him about in a wagon to make it seem like a game until walking was out of the question and Lucas was confined to his wheel chair. Gypsy could pull that, too. The boy and the dog had developed an affinity which Lucas's parents believed had helped to keep the boy alive.

On New Year's Eve, the Sixth Day of Christmas, it was agreed that an outing was possible. When he heard I was in town, a wealthy Mexican friend of mine extended an invitation to an afternoon gathering at his estate in suburban Guadalajara. It was ideal for the boys with its gardens spilling flowers into a vast artificial lake. We picnicked on a little island in the lake.

"His body has nearly spent itself," his mother pronounced sadly while the boys sat giggling together under a tree, "but his love for Gypsy renews his spirit every day, and Paco has been a tonic as well. They have both extended his life. Still, the end is near. His time could come at any moment."

Even so, no one was prepared when, two days later, on the Eighth Day of Christmas, Lucas suddenly died. It was as though we never knew it would come to that--the desolation, the pain in hearts left behind. The Gypsy queen and I were not there. We had gone to buy gifts for Twelfth Night. Lucas's parents were with him, and Paco, and Gypsy.

Lucas's mother described his passing to us disconsolately: "My son and Paco were sitting on the bed together playing a silly word game when suddenly Lucas fell back on the pillow. We were outside in the hallway. Paco shouted for us to come. Lucas lay very still, but his eyes were open, and he could talk: 'I think I have to go now. God must need me very much.' Paco lay with his head on the same pillow and would not let us move him away. 'No,' he said, 'I am going with Lucas. I must be here beside him where the angels of death can find me.' I told him he could not go, but he shook his head and pulled himself closer to my son. 'Mama is right,' Lucas said. 'I have to go alone. You must stay here to take care of Gypsy. He's your dog now. He will pull you around the way he pulled me. Mama, you will let Paco have Gypsy, won't you?' Of course, I said that I would. Then...my Lucas...told us...he loved us. And then ....he...was...gone."

We stayed on through the Tenth Day of Christmas, when they interred Lucas. We began the drive back to El Mesón early on Twelfth Night. Since Lucas's death, Paco had not been his usual chipper self. He had worn a back brace since the surgery, and hated it, but the problem was mental. When asked to tell us what was wrong, he barked, "I don't want to talk about it!"

"When does this thing come off?" he asked about the brace.

"The doctor said we should remove it only when you sleep," the Gypsy queen replied. "You are supposed to wear it for the rest of your life."

He sat in silence for awhile.

"Then I won't live very long," he snapped. "Stop the bus. I want to ride with Gypsy."

We stopped, and I carried him to a sitting area midway back where I strapped him into a chair. He begged me to loosen the new brace, but his mother said no. We had to follow the doctor's orders. Paco was an unhappy boy at the moment. Not even a lick from Gypsy improved his disposition. We continued on our way.

"I wouldn't worry too much, Doña Concepción," I suggested. "He has good reason to be out of sorts. He's upset about Lucas's death, and he hates the brace. Everything must look bleak."

She shook her head, keeping her eyes on the potholed road as she drove. "I know my son. It's something more, deep inside. We'll find out in time."

I had sent telegrams regularly to keep the people at home apprised of Paco's progress and of our return. Private telephones were a rarity. Most calls went through central exchanges in each town or to public phones. Hand-delivered telegrams were a useful service.

Everyone had gathered at El Mesón by the time we arrived. Despite the loving reception with kisses all round and endless hugging, Paco remained distant.

My dachshunds had already known and loved a German shepherd, named King, in Italy. He had taught them the lessons city dogs needed to know for country living. They took to Gypsy, and he returned the compliment after a lengthy session of sniffs. Afterward, they all sat quietly together near Paco while María served refreshments. She settled on a chair beside Paco to feed him herself. He shook his head wordlessly each time she lifted food to his mouth, keeping his lips closed. Wisely, she did not insist and gave up after awhile, but stayed at his side.

His depression seemed serious enough for Father Mateo to suggest extra medication.

His mother declined. "I want his mind as clear as possible. He's working something out in his head. It must be solved, or he will suffer even more. He is not like me and the tribe, or like anyone else I have ever known. He has an intensity I do not possess. He taught himself to read and then helped me improve mine. He can learn anything, and never forgets. His powers of concentration have frightened me sometimes."

Has he any formal education?" asked my Jesuit historian.

"Oh, no!" his mother replied. "We are never anywhere more than a week or two. His learning comes from books he reads on the road. Besides, who in this country would teach a Gypsy child with no arms or legs, a Gypsy child who is actually a Mexican Indian of the most despised class?"

My Jesuit touched her arm gently. "Dear lady, there are those of us who do not despise the Indian and who feel that having arms and legs is not necessarily the sign of a good mind. You should remember that the greatest leader this country has ever known was Benito Juárez, a political genius of pure Indian blood. His dark face shines like a white light in the history of Mexico."

Directly, as evening came on, José proceeded to light the lanterns strung across the courtyard. I wondered aloud if the Three Kings might have secretly delivered our gifts to the stable in the corral. Of course, José and María had already placed out there the things we brought from Guadalajara.

Paco tapped María's knee. She lowered her head. He whispered. She nodded. She rose from her chair, lifted him in her arms, and carried him to the corral. A look from María suggested that we not follow right away. I thought she might be taking him to the privy. I asked the Gypsies to honor us with Romany songs. The young girl about to be married sang a few lovely ballads, joined by the others. Then the nuns offered a charming duet of sacred music.

At that point, I heard María say to us from the archway, "He's feeling better now."

The figures of the Holy Family still stood in the crèche which would not be disassembled until the day after Epiphany, which is often the time when Christmas trees are taken down in the States. We found Paco sitting beside the cradle, as he had on Christmas Eve. The lanterns were lit as before, giving the effect of a theatrical tableau. He looked radiant, a complete turnabout from thirty minutes past. I took charge of passing out gifts. There was something for everyone.

The largest box, up to my waist, had Paco's name on it.

"Shall I open it for you, young man?" I asked.

He nodded, his eyes wide. I stripped away the wrappings to reveal Lucas's wheel chair, a gift from the parents of the dead boy. Paco beamed.

"I already knew about the chair," he said brightly. "Lucas told me just now. They've made him an angel, you see, so he makes round trips, now. He said they sent him to tell his mother in what she thought was a dream that God is giving her a baby to take Lucas's place. Lucas will be the guardian angel. They will always be together."

He looked around. Our faces showed clearly that we weren't sure how to respond.

"I tell you, it's true!" he insisted. "I asked María to bring me out here to talk things over with Baby Jesus. He was happy to see me again. Look at His smile!" He nodded at the carved figure in the cradle. "He told me Lucas had been waiting for me, and there he was, right there, sitting on top, shining brighter than these lanterns." Paco indicated the box which had contained the chair.

We all looked at the box expectantly.

Paco laughed. "María couldn't see him, either! He came just to talk to me. He knew why I wanted to go with him to heaven. We had talked about it. He knew I wanted to ask God why was I born like this, why I was made only halfway. I never forgot that my first mother abandoned me, and then, when the angels came for Lucas, they didn't want me. I thought even God had abandoned me. He would take a good, well-made boy like Lucas, but he had no use for a misfit like me. I really didn't like God anymore." An agonized sigh came from the Gypsy queen. Paco lifted his arm stumps entreatingly.

"No, Mamacita, don't be sad! I don't feel that way now! Lucas said heaven did not do this to me. I was meant to be a perfect child. Something happened, but no one knew until my first mother prayed over me when she left me on the hillside. Mamacita, you were the answer to her prayer! You needed me. God knew you would love me. I'm a lucky boy! My job is to love everyone as much as I am loved. That's all Lucas said, except that I have to keep on making the most of what I have, and if any changes are to be made, heaven will make them. Does that mean God will give me legs, Mamacita?"

Doña Concepción lifted him to her bosom.

"What could be impossible to infinite love?" she said.

I asked the same question of myself the following afternoon after being summoned to the telephone exchange to receive a call from Felipe in Guadalajara. He reported that Lucas's mother, in an almost hysterical state, had rushed into the clinic that morning crying her dead son had appeared in what seemed like more than a dream with the prophecy of another child.

A test in the laboratory confirmed her pregnancy. After recovering from the shock of this corroboration of Lucas's visit to Paco, I informed Felipe how it was that we knew about it before he did. Dubious at first, being as much if not more of a doubting Thomas than I, Felipe knew that I would not lie about such a thing, particularly as Lucas was his nephew.

Staying close to Paco and his Gypsy tribe promised deeper insight into a phenomenon about which the late Albert Einstein once spoke of as "the sensation of the mystical," making us want "...to know what is impenetrable to us really exists..."

Given that the Gypsies were leaving on a new tour through the mountains as soon as a fresh inventory of movies arrived from Mexico City, I wondered how to make the most of the few days left together.

The answer came when I returned to El Mesón to deliver the exciting news from Felipe. Paco and his mother were having bowls of María's delicious menudo, tripe soup served with a generous sprinkling of fresh oregano. As I approached the dining area unseen, I heard them ask María if she thought I might consider joining them for the first few weeks of the tour. Before the housekeeper could answer, I appeared in the doorway and shouted: "Yes! Yes!"

I could conceive of no more auspicious way to begin the new year.

|

|